Details of the planned trip

The route

During the 2006 attempt to sail singlehanded and non-stop eastabout round the world I had often wondered why nobody had tried to sail round westabout by heading up into the Pacific. It would initially mean rounding Cape Horn against the wind and current but once round then the whole way across the Pacific and Indian Oceans could be crossed in the warm Trade wind belt instead of down in the Southern Ocean. I knew people who had cruised round the world on an almost similar route but I didn’t know anyone who had done it singlehanded and non-stop.

It seemed worth a try and I began to do some research into it.

The traditional eastabout route involves sailing round the world in the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties, south of all the great capes; the Horn at the tip of Chile’s land of fire, (Tierra del Fuego), Cape Agulhas at the south tip of Africa, Cape Leeuwin on the SW corner of Australia, South East Cape on Tasmania and South West Cape on Stewart Island NZ.

The wind is predominantly from the west and fresh to strong a lot of the time with frequent gales. The prevailing westerly wind also means the current sets to the east continually as well. So, it suited the old clippers to sail that route round the world especially to Australia and New Zealand. To go westward along that route would mean sailing into the wind and current almost all the time. For good reason it has always been called, “The wrong way round”. Chay Blyth was the first to do it in a yacht solo and non-stop and it was a long hard slog. Elsi is not great at sailing to windward and it would be madness to even attempt that route with her. But a westabout passage down through the Pacific Trade winds would be a different option.

Heading north up into the Pacific from Cape Horn, instead of continuing westward would mean crossing the whole of the Pacific and Indian oceans in mostly fine weather with a warm SE trade wind at my back.

Looking ahead and seeing where I wanted to be at certain times would set the leaving date from the UK. Cape Horn is best rounded as near to summer (December/January) as possible although summer is a relative term down there. The cyclone season in the south west Pacific is from November to May so that had to be avoided. Likewise the hurricane season in the north Atlantic meant that I shouldn’t be re-crossing the equator, heading north, until after the end of September.

I looked at the route from every month, based on Elsi’s average speed, and a departure from the UK in early November seemed to be the best time to leave to tie in with being in the right place at the right time most of the way around. The shortest distance on the track I plan to follow will be around 32,000 nautical miles (nm) but the actual sailing distance to allow for sailing to windward etc will probably be nearer 40,000 nm.

The trip will take at least a year. Leaving Falmouth in early November I should be back there again in early December 2014. Ideally I would have started the trip from Shetland and sailed back there but with the start and finish in November/December there was the potential risk of an extra month of sailing in bad weather to the west of the UK at that time of year. So the best solution was to start from Falmouth.

Navigation

I will have three GPS’s (Satellite navigation systems) onboard but I don’t plan to use them very often. One is a stand alone GPS, another is part of a chart plotter built into my laptop and the other is built into the AIS (a ship tracking system) unit. Instead I plan to navigate, as far as possible, by traditional methods; sextant, compass and log line. This is what I did on the 2006 trip and it worked out fine. I never had to use GPS until SW of Australia when I had to give a precise position to the Australian Coastguard spotter plane.

I find it a far more satisfying way to navigate than just looking at my position on a digital readout. With the sextant I can usually get a position within about two miles. The GPS is undoubtedly far more accurate but out on the ocean if you know your position within about ten miles that’s near enough.

I do plan to use the chart plotter in the Torres Straits though. The navigation is tricky with so many low-lying reefs and irregular currents and I will be very glad of satellite technology there.

Charging the batteries

Before the 2006 trip I was struggling to work out how to carry enough fuel to run the engine to charge the batteries. Alyson suggested it would be an idea to take the engine out and rely on renewable power instead. It was a brilliant idea and worked really well. I didn’t have all the power I wanted all the time but there was plenty to keep everything working. There was always enough to keep the lights on and charge batteries to enable me to speak home almost every day on the radio and satellite phone.

This trip will be the same again but with more options. Last time I had an 80w solar panel, an Aerogen 6 wind charger and a permanent magnet alternator (PMA) fixed on a direct drive to the prop shaft where the engine used to be.

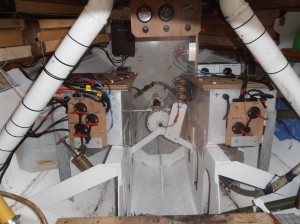

The propshaft (permanent magnet) alternator puts out ac volts which are converted to dc by the bank of rectifiers on the right before going into a charge controller and onto the batteries.

As Elsi sails along the propeller spins the shaft alternator. This alternator puts out ac power and a bank of rectifiers converts it to dc to charge the two large 210 amp hour batteries.

This time I am adding a 250w solar panel and I’ve made up a towing generator based on the same PMA used on the prop shaft.

Alyson has also loaned me her spinning wheel for the year. I’m not planning to spin a few fleeces as I go instead I’ve turned it into a treadle wheel to turn yet another PMA for the days when there is no sun or wind and the propeller is not turning.

Food

The bulk of the weight onboard is taken up by food to last me over a year. Most of it is in tins. There is enough onboard to give me 400 breakfasts, 400 lunches and 400 main meals. I could take dehydrated stuff, which would be a lot lighter, but then you must rely totally on having enough water to hydrate it and I don’t want to take that chance.

Recent Comments